The very first resolution of the United Nations, adopted by consensus in 1946, established a commission whose task was to make recommendations on the elimination at atomic weapons from national arsenals. 70 years later the world appears no closer to achieving this aspiration. Does this indicate a failure of the United Nations? Or an acceptance that nuclear abolition is an impossible goal?

According to Angela Kane, former United Nations High Representative on Disarmament Affairs, the lack of progress on nuclear disarmament is neither of the above, but rather a failure so far of governments and civil society to make use of the opportunities provided by the United Nations system.

During her term with the United Nations, Angela Kane made a number of presentations analyzing the international environment as it relates to nuclear disarmament, and discussing the role of the United Nations. These included a series of lectures in New Zealand, a presentation Creating the Conditions and Building the Framework for a Nuclear Weapons-Free World at a Middle Powers Initiative (MPI) event and a presentation Toward a Nuclear-Weapon-Free World: A United Nations Perspective at the annual assembly of Parliamentarians for Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament in Washington (click here for a full list of her speeches as UN High Representative).

She has continued to explore this topic in her new role as Senior Fellow at the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, including a recent presentation The United Nations and Disarmament: Fit for the task? (Vienna Speech)

Nuclear disarmament and the United Nations – success or failure?

On the first question – has the United Nations failed on nuclear disarmament – Kane suggests that the situation is nuanced with some successes and some shortcomings.

One success has been the containment of nuclear weapons to just a few countries. In contrast to predictions in the 1950s that nuclear weapons would spread to more and more countries, only nine countries have acquired nuclear weapons. This is nine too many, but still an indication of international restraint. The United Nations hosts the secretariat for the Non-Proliferation Treaty, and undertakes other non-proliferation action through the UN Security Council and UN General Assembly.

“The norm of non-proliferation has held up rather well, given the scarcity of States that are clamouring to acquire their own nuclear arsenals—far from it, the world’s 182 non-nuclear-weapon States support getting rid of them all.” (Kane, NZ Lectures on Disarmament Page 21)

Another success is that nuclear weapons have not been used since Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Perhaps the numerous UN General Assembly resolutions condemning the use of nuclear weapons as a crime against humanity and a violation of the UN Charter have contributed to this ‘taboo’ against use. Perhaps the International Court of Justice case which confirmed the general illegality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons has contributed. Perhaps a general awareness of the catastrophic consequences of any use of nuclear weapons – an awareness promoted by the UN – has also helped. In any case, this is a unique achievement amongst any weapons system – that a taboo against use has developed despite the lack of progress in elimination.

The UN has also assisted in negotiations for nuclear-weapon-free zones, which now cover over half the territories of the planet. “What these zones do is to help considerably in de-legitimizing nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction.” (Kane, NZ Lectures on Disarmament Page 8).

On the other hand the UN has appeared powerless to constrain the modernization programs of the nuclear armed States, the exorbitant funds spent on them annually and the continued policy of nuclear deterrence held not only by the nuclear-armed States, but also their allies under extended nuclear deterrence doctrines.

Conditions for nuclear disarmament – do we have to wait for Nirvana?

The nuclear-armed States accept the goal – indeed the obligation – to achieve nuclear disarmament, but argue that there are security conditions that have to be met before they can agree to the prohibition and elimination of nuclear weapons.

“Some demand a solution to the problem of war and armed conflict. Some demand a definitive end to all proliferation and terrorist risks. Some call for an end to missile defence. Some require a ban on space weapons. Some even call for world government. Etcetera… It would be quite an understatement indeed to say that a world satisfying all these conditions would not simply be today’s world minus nuclear weapons. Actually It would not even be a terrestrial world, but rather a description of Nirvana… Insisting on such preconditions for disarmament is viewed by observers as little more than a thinly veiled formula for postponing disarmament indefinitely.’ (Kane, Speech to MPI event, pages 1-2)

On the other hand, Kane recognizes that security concerns and conditions are important and do need to be addressed, but not necessarily in nuclear disarmament agreements. Rather, nuclear disarmament can take place in a wider disarmament and security framework which deals with these issues. Kane says that this is the framework of the UN Charter – which provides a range of mechanisms and approaches to resolve conflicts peacefully, and the legal requirement to do so. And it is complemented by the framework of General and Complete Disarmament (GCD), which is enshrined in UN resolutions and treaties such as the NPT, and which guides the regulation and disarmament of other weapons systems.

‘The framework of the UN Charter (and its related agreements) offers the best architecture for pursuing a world free of nuclear weapons. It is the framework of GCD reinforced by the Charter.’ (Kane, Speech to MPI event, page 3)

The UN Charter requires the peaceful resolution of conflicts – through conciliation, negotiation, mediation, arbitration, adjudication etc… and provides mechanisms for this. The UN also has a range of mechanisms to ensure compliance with international law and to facilitate the negotiation of disarmament agreements and their implementation. The problem is not the lack of a suitable framework and appropriate mechanisms, but insufficient commitment to using them.

‘Our challenge is not in building a new framework, but in implementing the one we already have. We need to ensure a better alignment of the policies of states with their commitments to GCD and the Charter.’ (Kane, Speech to MPI event, page 3)

Nuclear disarmament and the development of norms

Kane suggests that disarmament is achieved not only through mechanisms and agreements – but in the development of global norms. Indeed, a normative shift with regard to a weapons system usually precedes the negotiations for their prohibition and elimination. The use of chemical weapons was banned through the Geneva Gas protocol of 1925 after a normative shift following the use of chemical weapons in the First World War. Negotiations on a landmines convention commenced following deligitimization of them through widespread publicity of landmines victims.

The UN plays a vital role in the development of global norms. It does this through General Assembly resolutions, International Court of Justice cases, Security Council decisions, summits and conferences, reports, international days and other events.

“What makes the UN unique is that it is closer to universal membership than any other political organization… Legitimate norms are created through a democratic process of universal participation, to the extent that each member State – regardless of its size or level of economic or military development – has at least some voice in the development of these norms. It (the UN) has no rival as a source for the creation of global norms.’ (Kane Vienna speech, page 2)

Nuclear disarmament and global leadership

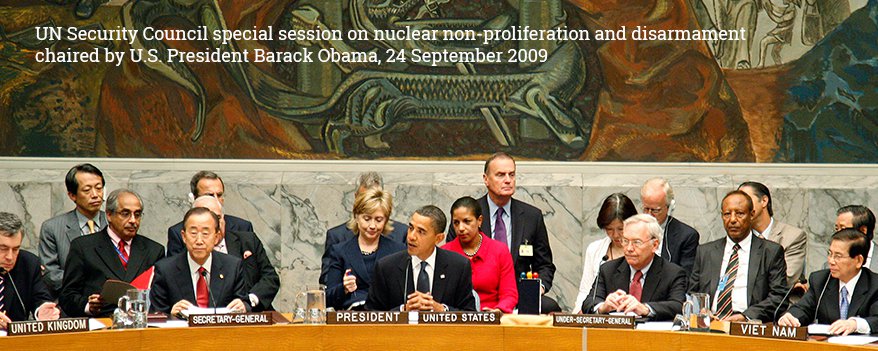

When world leaders advance nuclear disarmament, media and public take notice. The UN provides forums for world leaders to highlight the goal of nuclear disarmament and promote nuclear disarmament initiatives. This includes the annual opening of the UN General Assembly in September. The presentation by Pope Francis to the General Assembly in 2015, for example, was widely covered by global media and was very influential in building political momentum for the successful Paris Climate Change conference. US President Obama’s chairing of a special session of the UN Security Council on nuclear disarmament in 2009 was also influential in building agreement by all governments in the goal of a nuclear-weapon-free world. However, Mogens Lykketoft, President of the UN General Assembly, has remarked that world leaders are not making the most of this forum (See UNFOLD ZERO interviews UN General Assembly President).

Leadership is also provided by the UN High Representative for Disarmament Affairs and the UN Secretary General. Ban Ki-moon has undertaken a number of actions to highlight the importance of nuclear disarmament – including at Hiroshima and Semipalatinsk (old Soviet nuclear test site) and in releasing a Five-Point Proposal for Nuclear Disarmament. Kane was tireless during her term as UN High Representative, in promoting the Five-Point proposal globally.

The UN – shifting perspectives from national interests to global interests

An important function of the United Nations is to help governments shift from a solely nationalist framework to one that also embraces global interests. Many issues facing governments today are international requiring global cooperation – climate threats, refugees, ocean protection, financial stability, terrorism and nuclear threats. The UN provides a space for governments and civil society to come together to explore all viewpoints in order to develop sustainable cooperative solutions.

‘Representatives come here to advance their national interests, but they often find themselves having to consider the global interest—embodied in the great norms found in the UN Charter… These are often called “global public goods” and Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has called nuclear disarmament a “global public good of the highest order.” (Kane, speech to PNND Assembly, page 3).

Unfortunately, this opening to global issues and perspectives has not yet translated into a the profound shift in national priorities required to deal with these issues effectively. Despite an obligation under the UN Charter to reduce military expenditure in order to fund social and economic needs (Article 26), governments continue to invest over $1.7 trillion annually in militaries – and very little on the UN, diplomacy, aid and development.

‘The world spends more on the military in one month than it does on development all year. And four hours of military spending is equal to the total budgets of all international disarmament and non-proliferation organizations combined (including the United Nations). The world is over-armed. Peace is under-funded.’ (UNSG Ban Ki-moon, Seeking Peace in an Over-armed World). Until there is a shift in these national priorities, it will be difficult for the UN to fulfill its goals – including that of nuclear disarmament.

As such, ‘The United Nations wholeheartedly supports the Global Day of Action on Military Spending. It should encourage political leaders to reassess their country’s defense needs, explore confidence-building measures, and consider shifting priorities and resources for social, economic and human development.’ (Kane, Speech on the occasion of the Global Day of Action on Military Spending).

Conclusion

The United Nations has not yet delivered on the goal of nuclear elimination. Then again, nor have national governments. To its credit, the UN has played an important role in limiting nuclear proliferation, preventing nuclear terrorism and building a taboo against use. It provides forums for negotiating the elimination of nuclear weapons, and mechanisms to achieve security without reliance on nuclear deterrence. However, governments and civil society do not yet place enough importance on the UN system, nor is their sufficient political will for nuclear abolition. Greater public and political attention to the UN and the possibilities it provides, is vital if we are to succeed.

If we want to move forward, we – all of us – must dispel the myth that disarmament is just a utopian dream… If we can bring disarmament back down to earth as a practical and realistic way to strengthen national and international security and conserve resources to meet basic human needs, this is the road we must take without fear. It will be a long journey, but who better to travel the way than the United Nations, its independent civil service led by the Secretary-General?’ (Kane, Vienna Speech, page 3).