The May 2-13 sessions of the United Nations Open Ended Working Group on Taking Forward Multilateral Nuclear Disarmament Negotiations (OEWG) ended today with indications that a group of non-nuclear countries is ready to start negotiations in 2017 on a treaty to outlaw nuclear weapons.

The proposal was put forward by a group of countries that have already prohibited nuclear weapons in their regions through nuclear-weapon-free zones (NWFZs). 115 countries are part of NWFZs covering Latin America, the South Pacific, Antarctica, South East Asia, Africa and Central Asia.

Nine of these countries (Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico and Zambia) submitted a proposal to the OEWG to ‘Convene a Conference in 2017, open to all States, international organizations and civil society, to negotiate a legally-binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons’ and ‘to report to the United Nations high-level international conference on nuclear disarmament to be convened no later than 2018…on the progress made on the negotiation of such an instrument.’ (See OEWG working paper 34 – Perspectives from nuclear weapon free zones).

The proposal received support from a number of other non-nuclear States and civil society organizations during the OEWG sessions. However, none of the nuclear umbrella countries (NATO, Japan, South Korea and Australia) agreed with the proposal. The nuclear-armed States, who did not participate in the OEWG, are also opposed.

Many of the non-nuclear States participating in the OEWG argued that agreement from the nuclear-reliant states was not necessary to negotiate such a treaty. However, others argued that if such a treaty did not include at least some of the nuclear reliant states, it would have little or no impact on nuclear weapons policies and practices. Indeed, some argued that it could be counter-productive, taking pressure off the nuclear reliant states to adopt interim steps toward nuclear abolition.

Other options for nuclear disarmament negotiations were proposed that would be more likely to attract support from nuclear reliant states and thus impact directly on their policies. These included a ‘building blocks approach’ and a framework agreement similar to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, but for nuclear disarmament. Supporters of the framework agreement suggested that it ‘could include stronger prohibition measures early in the process, while still engaging those states not able to adopt such measures at the outset.’ (see Options for a Framework Agreement, Middle Powers Initiative working paper to the OEWG).

However, many non-nuclear States criticized the ‘building blocks’ approach and framework agreement proposals as not promoting sufficiently strong measures in the near-term. They argued that a clear prohibition treaty would be better even if it did not include the nuclear-reliant countries.

Eliminating the role of nuclear weapons

One of the main reasons that the nuclear-armed countries did not participate in the OEWG, and why the ‘nuclear umbrella’ countries do not support a nuclear prohibition treaty, is because these countries still rely on nuclear weapons for their security. The OEWG held useful discussions on the role of nuclear weapons in the 21st century and whether it’s possible to eliminate the role of nuclear weapons, including during current times of increased tensions and conflicts between nuclear-reliant countries.

A number of non-nuclear States and civil society organisations emphasized the possibilities for achieving security, reducing tensions and resolving international conflicts through alternative means. These include diplomacy, law, mediation, arbitration, adjudication and the use of common security mechanisms in the United Nations, Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe and other bodies. Some delegates noted that the recent agreement with Iran is an example of this.

Building political will – nuclear disarmament summits

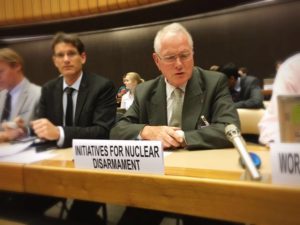

A number of countries and NGOs focused on a different issue – the lack of political will and commitment of the nuclear-reliant States to nuclear disarmament. The Middle Powers Initiative, Arms Control Association, Basel Peace Office, Parliamentarians for Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament and UNFOLD ZERO proposed a series of Nuclear Disarmament Summits in order to build such political will.

The proposal was inspired partially by the success of the Nuclear Security Summits, which built cooperation and commitment to prevent nuclear terrorism. The Nuclear Disarmament Summits – a series of bilateral (US-Russia) and multilateral meetings at head-of-government level – would enhance media and public attention to the issue and increase the pressure on nuclear-reliant states to adopt key disarmament measures. See Nuclear disarmament summits: Building political traction for the adoption and implementation of legal measures and norms, MPI working paper to the OEWG.

Where-to from now?

The OEWG will hold its final session for 2016 over three days in August (16, 17 and 19). It will then adopt a report to present to the United Nations General Assembly. It is unlikely that consensus will be achieved on either a prohibition treaty (the most popular proposal among the non-nuclear States) or the building blocks (‘progressive’) approach which is the most popular proposal among the nuclear-reliant states.

The proposal for a framework agreement might emerge as a compromise approach. If not, it’s looking more and more likely that a group of non-nuclear States will move ahead in 2017 to commence negotiations on a prohibition treaty regardless of whether-or-not and nuclear-reliant states participate.

Air Jordan 1 Mid Black White Shoes Best Price 554724-113 – Buy Best Price Adidas&Nike Sport Sneakers